Written by Arielle Randolph, MD, PGY-3 at Kaiser Permanente Oakland Pediatrics Residency Program while on Global Health…

Cacha Medical Spanish Institute – Eric Bautista, MD

Written by Eric Bautista, MD, PGY-3 at Kaiser Permanente San Francisco Internal Medicine Program while on Global Health rotation at Cachamsi in Riobamba, Ecuador in March 2017.

Global Health Background and Departing for Ecuador

I took off for Ecuador after my last night shift in residency. I left one of the most resource-rich and connected systems in the world and was off to experience medicine with much more limited resources. Being in a “developing country” is not new to me; my parents emigrated from the Philippines a year before I was born and I had spent some time back in the Philippines. I had also spent a summer visiting HIV organizations in India during college to investigate the impact of discriminatory laws against sexual minorities on the HIV epidemic there. Just this past year, I took a trip to visit my relatives in the northern tip of the Philippines. About a full day drive from Manila, it is a poor region of the Philippines that is not on the typical tropical tourist circuit. Having been to the Philippines multiple times in the past, I never recalled obesity as something I commonly encountered in trips in the past. This time was different. My family had asked many medical questions knowing that I was doctor: not about exotic tropical diseases, but about hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and arthritis. To me, “global health” for my family in the Philippines looked a lot like my practice in Kaiser. I was heading to Ecuador reflecting on this.

Ecuador: History, Politics, and Healthcare

In my perspective, knowing about a country’s history is crucial in understanding its people, culture, and current affairs. The Health system is born out of this social structure. Ecuador consists of 3 distinct regions: the coastal lowlands, the Andean highlands, and the Amazon basin. Prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, the Incan Empire in the Andean Highlands had expanded into Ecuador and just as the Spaniards had arrived, the empire had been divided between Ecuador and Peru. With the arrival of Francisco Pizarro and the Spanish colonialists, indigenous Incan rule had come to an end and was replaced by Spanish colonization and catholic missionaries. In the 1800s, Simon Bolivar and José de San Martín sought to liberate the South American countries from Spanish rule; Ecuador reached independence in May 24, 1822. For a few decades Ecuador was part of a larger region called Gran Columbia including Venezuela, Colombia, and Ecuador, headed by Simon Bolivar as an attempt to unify the region. However, the political system did not survive, and eventually the state of Ecuador was created in 1830. Until the 2000s, Ecuador’s political history was marred by corruption and an unstable government. In the 1990s, Ecuador’s former currency, the sucre, ran wild with inflation skyrocketing from 7000 per U.S. dollar to 25,000 per dollar over a year. Finally, in the 2000’s, Ecuatorianos elected presidents Jamil Mahuad and Gustavo Noboa who abandoned the sucre, and established the U.S. dollar as the national currency. Since then, Ecuador has enjoyed relative economic/political stability. Culturally, the demographic make-up today of Ecuador consists of 65% mestizo, 25% indigenous, 7% Spaniard, and 3% black. The legacy of the catholic missionaries remains with over 80% of the population identifying as Catholics.

From 2006 to 2014, the poverty rate had declined from around 40% to 22.5%, partially stimulated by GDP growth from strong oil prices and social services spending. Ecuatorianos are provided a universal health care system, dating back to 1967. After the the economic and political stability afforded by backing the country with the dollar, Ecuatorianos are provided free healthcare since 2008.

Clinical Experience

RIOBAMBA AND CACHA

I was greeted warmly by the Program Director, Pablo Martinez, and the next day was introduced to my Spanish tutor, Edith, and the medical team that I would be working with. For the month, I lived in the city of Riobamba, and worked in nearby clinics in the indigenous villages of Cacha in the mountains. Riobamba is a medium-sized city of 150,000 in the central Andean Highlands about 4 hours drive south of the capital city of Quito. It is a safe city with little tourists, and at an elevation of 9000 feet, it took me a good week before daily fatigue, headaches, and the ability to run more than one block cleared up. Cacha is a collection of villages 20 minutes up the surrounding southwestern mountains of Riobamba. While Riobamba is a solid middle class city and enjoys the modern amenities afforded by a city, Cacha is agrarian based and retains its traditional Quichoa culture. Eventually the roads up the mountainside give way to gravel paths, and people adorning traditional woven ponchos and hats, signaled that you were entering the community.

HEALTHCARE IN CACHA

As mentioned above, Ecuador has a universal healthcare system run by the department of public health. Community health centers, called Centros de Salud, provide primary care for the community. Hospitals and Specialists are based in major cities including Riobamba, and require referrals from the centros de salud for consultation. Of course, ERs exists for emergencies and ambulances are available in urban areas (In Cacha, we had transferred a teenage boy from clinic to the hospital in a taxi for concerns for appendicitis). While there is universal healthcare, care in Cacha and rural areas is still limited by geographic isolation and financial resources. I took inventory of the pharmacy (see table below). There are no labs services available in Cacha, and patients require a trip down the mountains into Riobamba. These are all the tools available to the medical team.

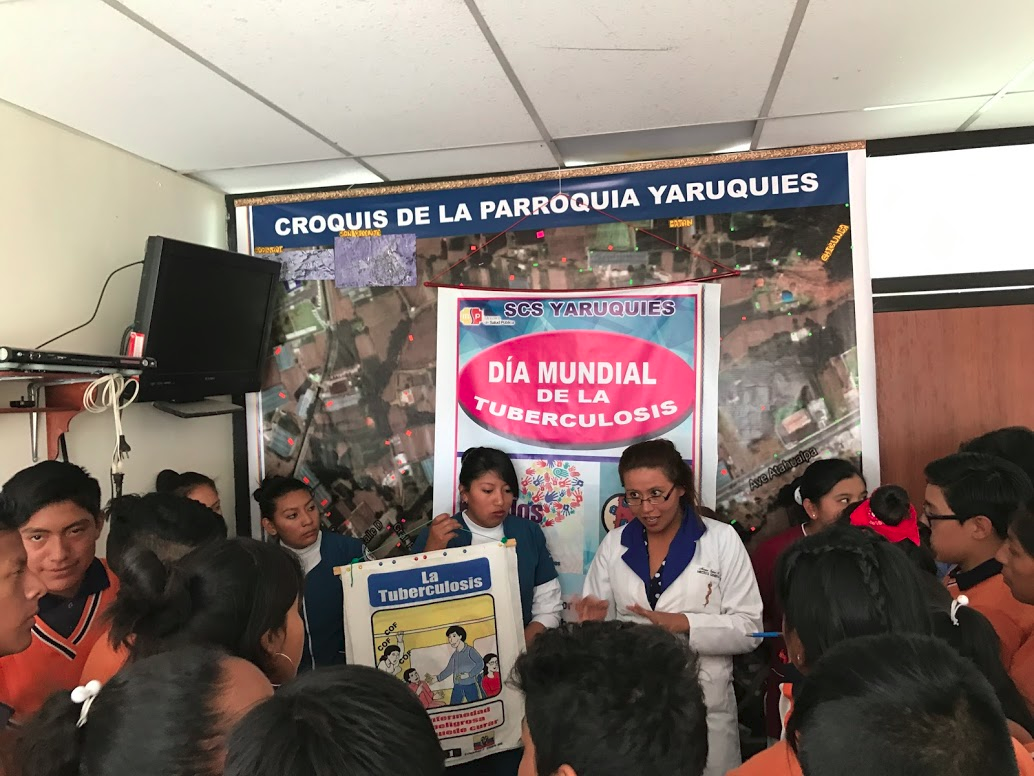

The team providing care to Cacha consists of 2 medical doctors, Dr. Rosita Tiupul and Dr. Mayra Calero, 1 dentist, and handful of nurses and assistants. As mentioned earlier, Cacha is a collection of pueblos, and everyday we rotated to a different pueblo for clinic or other public health initiatives. As a public health team, the responsibilities of the doctors and team expanded beyond clinic duties and involved other public health initiatives. During my time in Cacha, we also went to schools to provide well checks and vaccinations, gave public health talks to schoolchildren (world TB day), and drove around the mountains with a speaker tied to a car roof vaccinating dogs and cats to prevent rabies transmission. Other responsibilities of the team include community emergency planning, home visits (geriatric and prenatal visits), and community health activities.

NSAIDS: Ibuprofen Acetaminophen IM diclofenac Aspirin Vitamins/Minerals: Vitamin B Multivitamin Vitamin A Folic acid Iron Beta blocker: Atenolol Blood pressure: Enalapril Cholesterol: Gemfibrozil Simvastatin Reflux: Magnesium hydroxide Simethicone Ranitidine Omeprazole Calcium carbonate Allergies: Loratadine Inhalers: Albuterol Steroid creams: Mometasone Betamethasone |

Antibiotics: IM penicillin G Amoxicillin Ampicillin Azithromycin Augmentin Sulfamethoxazole / Trimethoprim Cephalexin Clarithromycin Ciprofloxacin Nitrofurantoin Antifungals: Clotrimazole Fluconazole Antivirals: Acyclovir Antiparasitic: Albendazole Tinidazole Antifungal creams: Clotrimazole Nystatin Terbinafine Rehydration: Electrolyte solution Eye drops: Tobramycin/dexamethasone Contraceptives: Levonorgestrel Ethinylestradiol and levonorgestrel Condoms |

Table 1. Medicines available at Cacha Clinic

CLINIC CASES: A STANDARD DAY

The 2 doctors in Cacha are trained in family medicine, so are able to see anybody in clinic from pregnant woman to newborns to children and the elderly. The standard day in clinic, depending on the pueblo, could be very busy with up to 15 patients for one doctor in the morning (compare this to the 12 patients I see in a standard day as a resident). Complaints were familiar: prenatal checks, newborn checks, well child checks, viral URIs, hypertension checks, diarrhea. While I did not ask particularly, antibiotics were used much more liberally compared to the U.S.; in a patient with cough, congestion and sore throat amoxicillin was given freely; somebody with diarrhea was given not only cipro/flagyl but also a course of albendazole; lower abdominal pain but without urinary symptoms were treated empirically for a UTI. Again, ancillary resources are limited, and requesting labs meant asking a patient to make a trip down the mountain into Riobamba. Deciding to empirically cover for infection was a risk/benefit analysis and weighed out the practical aspects, feasibility and risk for loss of follow up with further workup.

CLINICAL CASE: PARASITE PREVENTION

During our well check trips at the schools, children were given prophylactic albendazole every 6 months. I was curious about the epidemiology and evidence by this intervention. A study in North India by Awasthi et al had looked at pre-school-aged children and compared groups receiving albendazole versus control every 6 months. The nematode egg prevalence had decreased from 36% to 16%, and there were minor changes in weight difference between both groups (3-year-old’s both 12 kg in treatment group compared to control group; and 6-year-old 72 kg in treatment group compared to 68 kg in control group). In addition, a meta-analysis by Taylor-Robinson et al did not demonstrate an association between deworming and child cognition, school attendance, and school performance. However, despite these findings, population deworming is used given associations between helminth infections and delays in growth and cognitive development among children.

CLINICAL CASE: MATERNAL AND NEONATAL MORTALITY

One day in clinic we had one woman walk into clinic with a newborn in her arms. She looked to the doctors and said she gave birth just a few days before at home. When asked if she received medical attention and had paperwork, she said said no. The doctor and Ecuadorian resident working with us that day looked at each other, and after explaining retrospectively the risks of not seeking standard care, conducted a newborn and postnatal visit. As a follow-up, we made a home visit later that week. It was a modest-sized dwelling consisting of 2 rooms, and we met the mother and baby lying in bed. The baby was having difficulties feeding, had sunken fontanels, and cold extremities. The team counseled the mother on breastfeeding, and warmed hot packs to warm the baby. Unfortunately, my ride down the mountain arrived before the end of the visit. During my time in Ecuador, I was told that Ecuador had a high rate of maternal and neonatal mortality. Looking into it further, maternal mortality is estimated at 64 per 100,000 live births in 2015, ranking 87 out of 182 worldwide (with 1 being the highest mortality). Neonatal mortality rate is 10.8 per 1000 live births in 2015, ranking 95 out of 182 worldwide.

MEDICAL SPANISH

One of the biggest draws of the Cachamsi program was the opportunity to work on my Spanish. For 2.5 hours every weekday, I had one-on-one sessions with a teacher to learn medical Spanish. Sessions were divided between Spanish grammar and vocabulary and learning to conduct a clinical visit in Spanish. We were taped in the beginning without warning to attempt a clinical visit in Spanish; reviewing the tape was somewhat torturous as I watched myself struggling to communicate with hand gestures. By the end, we did the same exercise and I could conduct a complete exam from history to physical to counseling. I still have a long road ahead in terms of fluency and comprehension, but comparing these two videos was dramatic. Due to my competency in Spanish most of the actual clinical encounters above were mostly observational, while I would occasionally help with the physical exam. For participants with better fluency, there was more opportunity to conduct the full visit. However, to protect the doctor-patient relationship, practicing Spanish without full fluency prevented me from fully conducting exams on my own.

Reflections on Global Health

In many ways, the Cachamsi rotation is an ideal model to experience “global health” for medical residents. Part of this statement also begs the question of the definition global health and responsible medical practice. Rather than descending on a community as an outsider to provide a one-time service, I instead was joining an established system that would be able to provide continuity of care. I was joining a team of doctors that knew the community well and that knew how to navigate the social implications of its culture when practicing medicine. While the aims of global health are noble in improving health outcomes worldwide, policy must always take into account the unique cultural and social context of a region when implementing medical interventions. My experience provided me a glimpse of what caring for a community means, even within the confines of limited resources.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Awasthi, Shally, et al. “Population deworming every 6 months with albendazole in 1 million pre-school children in north India: DEVTA, a cluster-randomised trial.” The Lancet 381.9876 (2013): 1478-1486.

Ecuador. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ecuador.

Ecuador: Overview. http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/ecuador/overview.

Health Status. World Data Atlas. https://knoema.com/atlas/topics/Health/Health-Status/Neonatal-mortality-rate?baseRegion=EC.

Mejia, Rojelio. Mass drug administration for control of parasitic infections. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/mass-drug-administration-for-control-of-parasitic-infections?source=see_link.

Taylor, Robinson, David C., et al. “Deworming drugs for soil‐transmitted intestinal worms in children: effects on nutritional indicators, haemoglobin, and school performance.” The Cochrane Library (2015).