Written by Christina Kinnevey, MD, Fellow at Kaiser Permanente Napa-Solano Community Medicine & Global Health…

Hospital de la Familia – Brian Song

Written by Brian Song, MD PGY4 at the Kaiser Permanente Oakland Otolaryngology Residency Program while on global health rotation at Hospital de la Familia in San Marcos, Guatemala in March 2015.

The weekend before our departure to Guatemala, we gathered at a team member’s home to organize and pack our supplies for the trip. In between glasses of wine and introductions, we stuffed bags and boxes full of sutures, surgical instrument trays, sterile gowns, and beanie babies (for the children of course). The team consisted of many returning veterans which became evident with the high level of organization during the packing process. Each box was strategically packed, weighed, and labeled so we could maximize every square inch of space in the minimum amount of boxes. Throughout the party, many of the veteran team members reminisced stories of past missions and the surroundings shenanigans that filled the nights. Anticipation and excitement filled my mind.

On the day of departure, the mission wasted no time before presenting its first hurdle. As we checked in for our flight, we discovered there was a previous miscommunication regarding airline policy and our supply boxes were all over the restricted weight. With only an hour until boarding time, we tore through the boxes and haphazardly re-stuffed the boxes to make weight. The previous weekend’s meticulous packed boxes were now bloated amoebas liberally wrapped with clear packing tape to prevent the boxes from bursting open. One of the veteran team members looked to me and saw the trepidation expressed on my face. With a twinkle in his eye, he reassured me that it’ll be ok stating,”its Guatemala”. While we were still in the United States and his words did not quite make sense, I understood the sentiment. The trip would be challenging and adaptability will be essential to make the trip a success.

On the flight over, the fatigue of residency overwhelmed me and I slept the majority of the flight and bus ride to Nuevo Progresso, Guatemala. When I did manage to stay awake and socialize for short periods of time, one of the other team members showed a candid picture of me with my head contorted back and to the side with my mouth gaping open. I was horrified and amused. The team was already showing its playful colors. As the days of the mission passed by, I realized it was this lighthearted spirit intertwined with a purposeful attitude that made the trip so effortless despite the high volume of patients and low resources that we had to overcome.

After many hours of travel, the bus pulled up to hospital and the locals greeted our arrival with a display of firecrackers. The loud blasts were at first unsettling but a nice gesture. Similar to an officiant firing a gun to start a race, the firecrackers marked the official start to our medical mission. As we unpacked the bus, the empty streets and quiet clinic were one of the few moments of calmness before the flurry of patients that awaited us in the coming week.

Each morning at the crack of dawn, we started our days with a morning hike to the outskirts of the town. We passed by small tin roofed huts, a multitude of stray dogs, and tiny tricycle taxis called tuk tuks. These morning tours gave perspective to how little resources the local population thrived on. Yet, despite having few material possessions, they had big hearts and always made us feel welcome with sincere smiles and waves.

As we returned from our hike and approached the hospital, one could hear a growing hum of a crowd nearing. When we turned the corner, the once quiet hospital now looked like a crowded marketplace with patients filling the courtyard of the clinic and spilling into the street. Small street side vendors lined the entrance of the clinic providing food and drinks for the patients who often waited hours before seeing one of the doctors. Walking through the crowd in our hiking clothes, I couldn’t help to feel a twinge of guilt for taking a moment for ourselves on our walks while these people, whom many traveled hours to reach the clinic, waited anxiously for our return.

When we finally opened the clinic doors, a stack of 40 patient charts awaited our attention. So it began. Obtaining accurate histories was very challenging. Trying to decipher notes from paper charts which were often written in Spanish with a doctor’s stereotypical hasty handwriting was difficult. In these moments, I really appreciated our home institution’s electronic medical record system. Interpreting patient histories from the patients themselves was even more challenging. Limited to a few broken Spanish phrases and questions in my quiver of Spanish vocabulary, I had to lean heavily on my physical exam and my co resident, who is a fluent Spanish speaker, to investigate underlying medical problem. We maximized our small clinic space and evaluated two patients at a time and sometimes a third. Occasionally, I would even take a patient into the clinic bathroom and shut the door in order to create a somewhat quiet environment to appropriately evaluate their hearing. One by one, we cleaned out cerumen from a multitude of ears, performed endoscopic laryngoscopy exams, and signed patients up for surgery. Exam after exam, patients left with a gracious handshake and a thankful smile. Spanish phrase after Spanish phrase, my Spanish fluency…well…improved a little.

The operating suite was a completely different world from the hectic clinics. Right when I walked through the double doors, the cool air and soothing music embraced my senses. Here in Guatemala, the OR became my escape haven; it was controlled with only one patient to focus on and, to be honest, a mini vacation for my brain from the taxing efforts of trying to obtain accurate histories with my minimal Spanish skills.

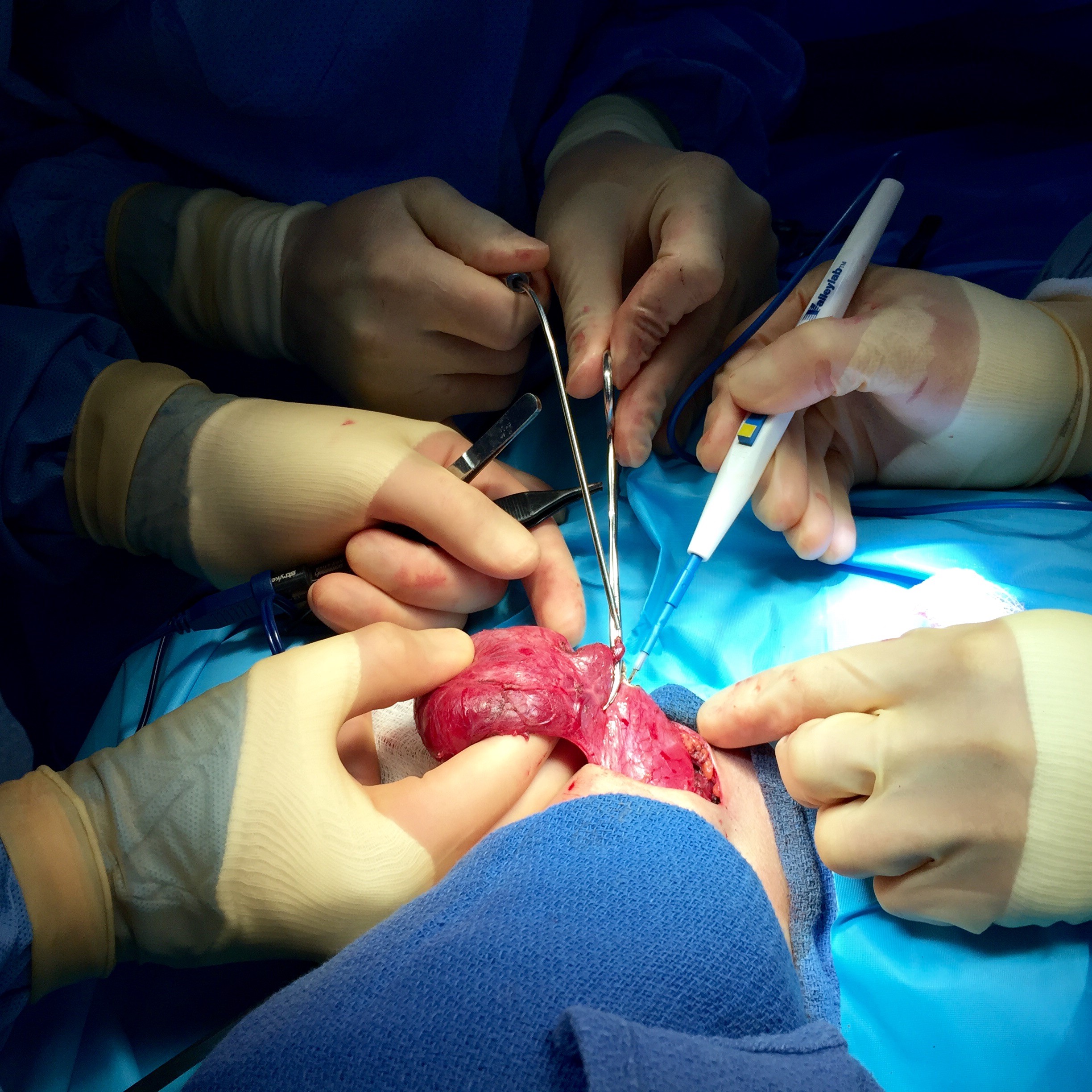

The OR in action was truly inspiring. Side by side, four operating tables and their respective surgeons worked in parallel. On one side of the room, the plastic surgeon adeptly repaired a cleft lip while on the other side, the ob-gyn surgeons worked to address a woman’s uterine prolapse. As the day carried on, surgeons started to break away from their own tables and drifted over to other

tables to see what the other surgeons were performing. And why not, it was only a couple of steps away. An ob-gyn surgeon started asking about some of the cautery instruments we used in head and neck surgery. She shared some of her techniques to retract skin. The plastic surgeon gave his advice on a facial flap. The general surgeons inquired about our philosophies on drains and thyroidectomies. Discussions and cross pollination of surgical techniques started to flourish right before my eyes. As the week progressed, these discussions evolved into diverse surgical teams. The urologist was scrubbed alongside the general surgeon to repair a hernia. An ob-gyn resident assisted in removing a gall bladder. I joined the plastic surgeon in repairing a cleft palate. It was the medical environment that I had always fantasized about, ego less collaboration with just the objective of helping the patient at hand.

In the end, we treated hundreds of patients and performed over a hundred surgical procedures in just over a week. And while I initially thought the lines of patients would never end, the last days saw only a trickle of patients coming through the doors. On the final day, goodbyes were said and pictures taken. We then embarked on our trip back home. Yet, on the trip home, it felt different. New friendships were made and laughter filled the bus. There was a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment. And despite the physical exhaustion, I felt re-energized with my passion in medicine and hope to carry the lessons learned with me to the patients here in our local community.

This Post Has 0 Comments