Written by Hongyu Zhao, MD, PGY-2 and Qing Meng Zhang, MD, PGY-2 at Kaiser Permanente…

On the importance of cultural knowledge

8/22/12

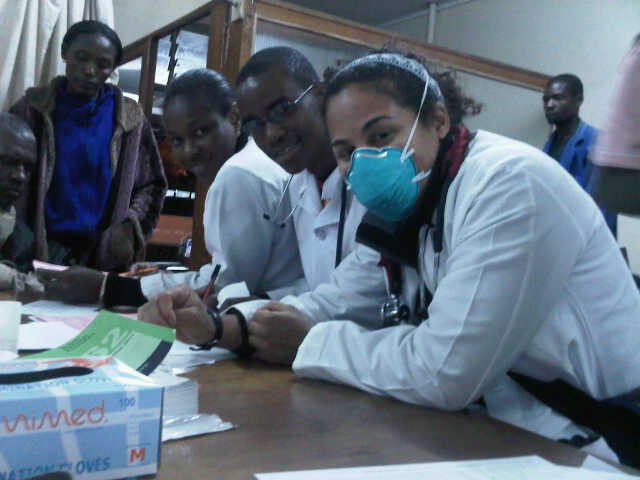

Posted by Amanda Thornton, MD (a third year Internal Medicine resident from Kaiser Permanente, Oakland while on a global health elective in Lusaka, Zambia with University Teaching Hospital).

My previous blogs have focused on the medical side of my time in Zambia. In this post, I’ll try to show the rest of the things I’ve been doing. I thought that it was very important, from the beginning, to make a real attempt to understand the background of my patients at UTH- where they lived, what their shared experiences were and what they expected from health care. I also tried to explore the medical culture here- how the training for residents and physicians work. I’m not a native Zambian and there’s no way I can absorb all the cultural knowledge that comes from living here for longer, but I learned a lot.

First- my parents requested that I mention any traditional medicine I have seen here. There are only two signs of traditional medicine that have been pointed out to me- both not accepted at all in the medical community. Sometimes when a patient comes in and on exam, it is discovered they have a string tied around the part where pain started. So patients with pelvic or belly pain sometimes come with a band tied tightly around their abdomen, patients with a foot ulceration come with a band tied around their ankle. This has not been looked upon positively by the physicians- it does not seem to relieve the pain and can occasionally cut off precious blood supply. The second is black scratches in rows, neatly done with a razor blade dipped in “medication” over the affected organ- a lady with chest pain or hypertension might have them on her chest. Traditional healers make these sharp cuts in the surface of the skin to apply their medication- unfortunately they do not always change their blades and sometimes patients who frequent traditional healers contract hepatitis B.

For the most part I’ve seen few people refuse Western medical care- other than performance of lumbar punctures- however some of my attendings have pointed out that traditional healers are more accessible to people, have more time to spend with their patients and are no where near as expensive. One of them also mentioned that there were several religious sects in some portions of Zambia who refused all vaccines, including ones for measles and as a result, there have been outbreaks when herd immunity no longer was effective.

I’ve learned a lot from my fellow residents and medical students, many of whom are native Zambians, both through discussion and by listening to what they tell me about their training. My American manners- my directness and unbridled inquisitiveness without fear of appearing ignorant- are very different from manners here, where people are soft spoken as a rule and no answer is better than the wrong answer. The culture in the hospital is traditional and occasionally intimidating to medical students, but that does not stop anyone from applying to shadow or work at UTH. Whether they are training in another country and wish to practice in Zambia or completed with their training and trying to obtain and internship at UTH- an assignment in the hospital is considered very prestigious and the best training to be had in Zambia.

If a medical school graduate is accepted to an internship at UTH (by navigating through an interview process including an oral exam on commonly found conditions in patients here), they have a 4 month provisional period to learn the system before they start to receive payment for their services. Many physicians from the Democratic of Congo have migrated to work in Zambia due to civil unrest, and native Zambian medical students may train in Russia, China, or elsewhere before coming to UTH- so this interview and provisional process is meant to ensure that all physicians have comparable training prior to being able to operate without supervision.

The intern year here is actually 1.5 years, and physicians in training rotate through all the major sections in the hospital: surgery, obstetrics, pediatrics and internal medicine. Then they receive a rural placement, where they are expected to see adults and children and where, according to my attendings, their independence truly begins. Then these post-graduates can apply for positions at hospitals, including UTH- where every physician who practices in Zambia should have rotated through at some point during their career. From there, if they are interested, they can try to write papers or do research to demonstrate interest in a subspecialty such as neurology or oncology before they apply for further specialized training.

I have not spent all of my time in the hospital, and I have not been idle during the days I did not have work. On the first weekend, I took the bike from my host family house and went on an epic search for a map and a bike lock. The roads are not equipped with bike lanes or shoulders and there are only occasional sidewalks which were often too rough for even my Zambike. Only a few Zambians know how to ride and bikes are nearly prohibitively expensive and frequently stolen. It was perilous to bicycle at all because people driving cars are not used to sharing the roads with bicycles, and not all the street names are labelled. While Googlemaps shows many roads, the ones shown have only a passing resemblance to the actual places. There is a local saying here: As long as you have a mouth, you a never lost. I learned to ask for directions.

On my search for a bicycle lock the first weekend, I ended up getting horribly lost in the shantytown part of Kalingalinga. During the dry season red dust blows everywhere and anyone who doesn’t have a car is covered in it from head to toe within a few hours of washing- I learned that this makes it very easy to tell who is privileged and who is not. No one paid any attention to me even deep in the poorest part of the town. This is possibly because I am mixed- according to my host, not too many years ago, children would have followed me around yelling “Za yellow,” a slang word for mixed race people. Later in my stay, as my grasp of the local accent improved, people would ask what tribe I was from- and laugh at my confusion.

Every time I got the chance, I spoke to people- taxi drivers, medical students on my team, and people I met asking what they thought about the health care system and how they used it. Most people with well-paying jobs go to private clinics prior to going to UTH, but very few people purchase health insurance. Everyone I spoke to is aware of the effects of HIV and AIDS- in fact it was rare that someone I spoke to had not had a family member or friend die from the disease as it decimated families. My heart went out to the AIDS widows who had seen or provided care for their husbands or fathers as they died, sometimes in great discomfort, and were resigned in their fate to follow them.

Though everyone agreed that HIV was a very big problem, no one was sure what the best solution was. The culture is not one that is naturally open about talking about sexual activity, condom use and frequent testing is low within married couples in whom fidelity is anticipated but not always found. Even within families, HIV status may be kept private as a stigma still remains.

While I was here, I also joined an Ultimate frisbee group full of Americans, South Africans, British and Zambians. They proved to be a wealth of information as well- many worked in health care or health care data, some in government agencies. They taught me a lot about the slang used here and the intricacies of being a foreigner.

I’m indebted to my host here for suggesting that I join- and to her family for sharing their cooking knowledge. I learned how to make nshima- a thick paste of boiled millet flour which is eaten with nearly every meal and “rape” cooked tangy dark green leaves which I suspect have no American equivalent. In return, I taught my hosts how to make the brown bread I’ve been making here as I could find no whole wheat bread in the supermarket- only brown flour.