Written by Arielle Randolph, MD, PGY-3 at Kaiser Permanente Oakland Pediatrics Residency Program while on Global Health…

Name, Insurance, and Neighborhood – Tessa Stecker, MD

Written by Tessa Stecker, MD Fellow with Kaiser Permanente Napa-Solano Community Medicine and Global Health while on rotation with Cachamsi in Riobamba, Ecuador in October 2015.

What is your name? Do you have insurance? What is your neighborhood? These three questions begin every clinical encounter in Riobamba.

The Ecuadorean health system has undergone an immense and impressive transformation over the last 15 years. Ecuador has become one of the leading countries in the region (and in the world) regarding healthcare efficiency spending (surpassing the U.S. by at least 30 spots on the world rank list). One of the reasons for this success is the strict adherence to patient centered medical homes. Each Ecuadorean is assigned a doctor/clinic based on his/her address and is expected to visit this clinic first except for in an emergency.

The clinic I’m assigned to this week reminds me of a bustling county clinic. A triage area in the main lobby determines if patients will be seen by a physician in the clinic, if they’ll be redirected to their primary clinical site, or if they’ll be sent to the ER. Patients and families sit in metal chairs along hallways awaiting their turn.

Dr. Patricia, the medical director, is gracious and kind enough to orient me to the clinic. Her office is also the exam room with a table in the far left corner of the room. In the morning, salsa music can be heard right outside the window as the Zumba class starts. Routinely as she sees patients, staff and colleagues come in to ask questions, get paperwork signed, etc. Rather than disrupting her morning, there seems to be an ease and rhythm to the flow. A few times, Dr. Patricia herself walked into a colleague’s office to ask a question while her colleague was in the middle of seeing a patient. But patients and colleagues alike appear unbothered. This open and genial atmosphere gives the clinic a sense of familiarity and ease.

The clinic sees a variety of patients of all ages but particularly a high number of teenagers – specifically teenage girls. The teen pregnancy rate in Ecuador is high. As Pablo (my medical Spanish institute liaison told me this morning), “if you come to clinic at 19, they will ask how many children do you have. One is normal by 16. If you are 26 and don’t have children, it’s considered shocking” – (to be fair, Pablo actually just shook his head in a way that conveyed the rarity of the without-child 26 year old) …duly noted Pablo, I’ll keep my child-bearing status to myself :/

Specialty care can be found in the large hospitals but is not always easy to access. As Pablo explained to me, the specialist may have 80 patients to see for the day but will quickly triage them and tell about 60 of these patients to “come back in 21 days” – a polite way of letting the patient know that their issue isn’t acute enough to warrant specialty care.

At lunch today, Pablo and Valeria (my Spanish professor for the week) took me to the supermarket to buy groceries for the week. My bed and breakfast has a kitchen where I can cook lunch and dinner. I made sure to pick up some summer berries (or maybe they’re called golden berries), a quinoa-rice mixture to go with the beans and plantains, and traditional Ecuadorean seasonal berry juice.

As we headed back to my B&B to deposit the groceries, Pablo proceeded to describe to me how I could get back to the market. I was following for the first two turns but then lost my sense of direction so I asked him for the name of the street we were on. He paused: “Oh, I don’t think there’s a name.” He must have seen a slightly panicked look on my face because he quickly explained that I could easily take a taxi there as well. Always good to have a plan B.

Tomorrow I might be seeing patients in conjunction with a visiting South Carolina physician but I may have missed the full description that was given in rapid-fire Spanish. Having spoken a total of 15 English words in the last two days (and yes, that means ultimately I’m speaking far less than usual), I’m mentally wiped but excited as well. In a city where English is very limited, I can stumble, mispronounce, and incorrectly conjugate my way through the day in Spanish. And sometimes, to my surprise, I string together the correct words, in the correct order without extreme difficulty. For this, I must heartily thank my Spanish professor for her patience and encouragement.

Ecuador: Sin Muertes Maternas

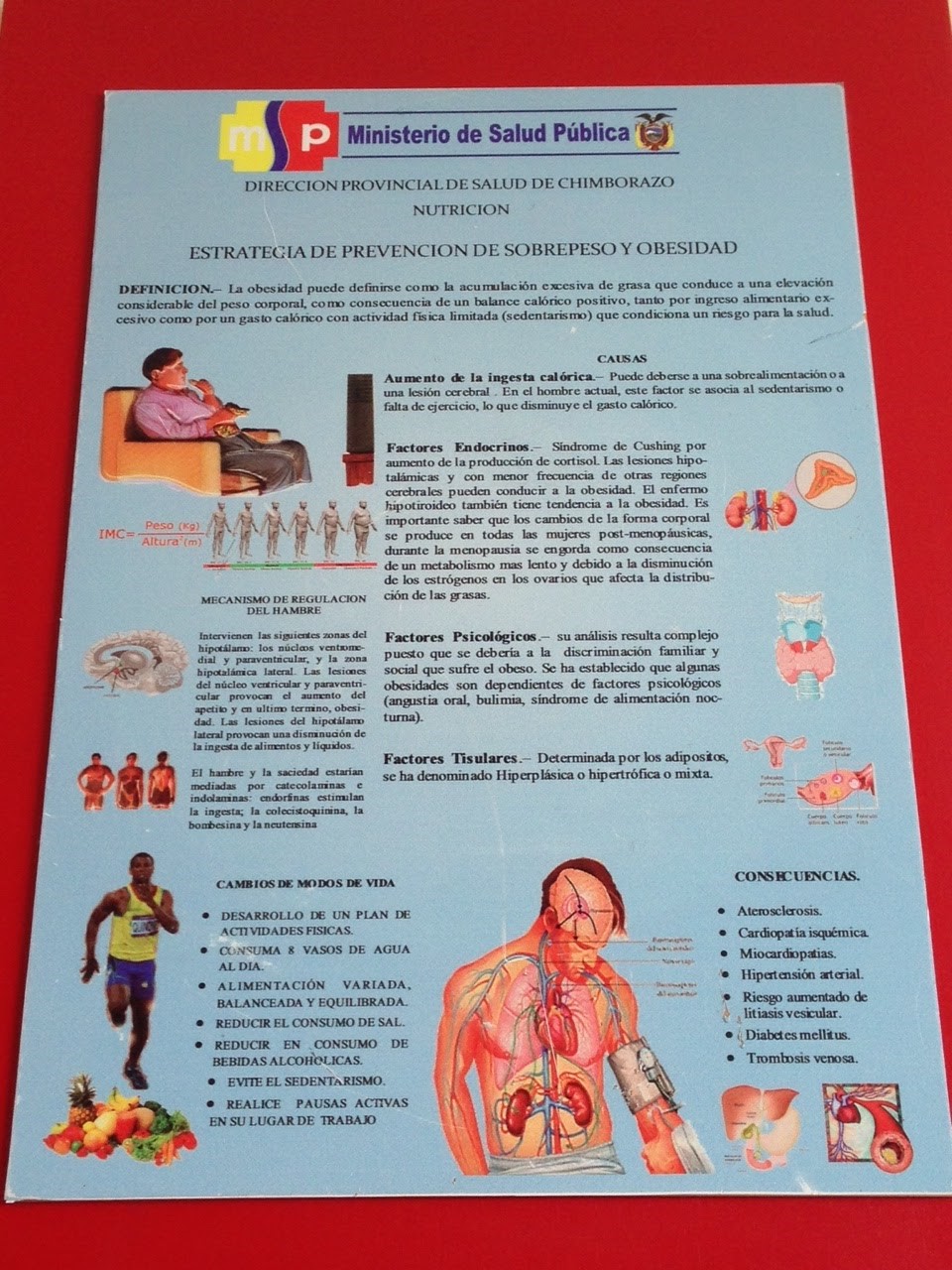

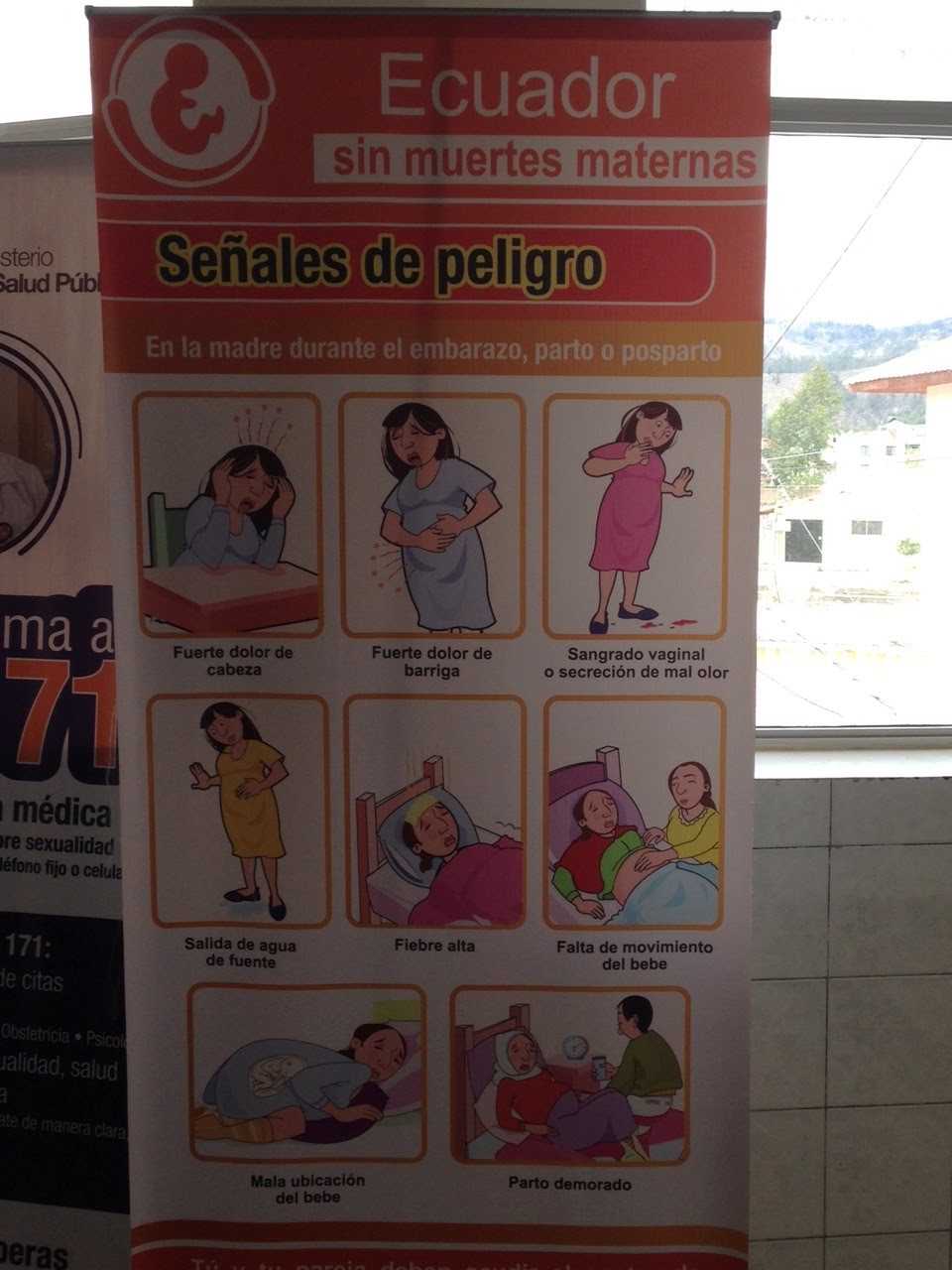

There exists an inextricable link between the public health department and the community clinics in Riobamba. The clinic is divided into departments based on the biggest community health needs: vaccines, maternal health, chronic diseases, nutrition, etc. There is an entire room which simply houses statisticians. The wall just to the left of entering the room is covered with various graphs, pie charts, and tables depicting current health trends and the incidence/prevalence of various conditions. This information is collected directly at the clinic and helps to inform how services and resources will be distributed. Throughout the clinic, public health signs caution against the symptoms of tuberculosis, provide tips on preventing obesity, and note the warning signs of preeclampsia/eclampsia.

Maternal mortality is one of the most serious health problems throughout the country and the large number of teen pregnancies contributes largely to the high numbers. In many ways, Ecuador has made significant strides in addressing the health needs of its people, but in this area the struggle continues. The public health campaign is battling against a tide of currently accepted cultural behaviors.

Community clinics blatantly advertise various contraceptive options – OCP’s, Implanon (nexaplon isn’t being used yet), IUD’s, etc. Undoubtedly, in parts of the country where access to medical services is harder to come by, decreased use of contraception is understandable. But in areas where services are readily available, what are the barriers to use? I suspect that some of the reasons are the same as in the states – lack of pre-planning, inconsistent use, fear of side effects, costs, privacy concerns. But in Ecuador, the cultural norm of teen pregnancy plays a large role. Simply put, teen pregnancy isn’t considered unusual. While on one hand, this ensures that many teens have the support of their families during pregnancy and in caring for their children; on the other hand, this relative normalcy makes it difficult to counsel young women regarding the severely increased risk of maternal complications and prevent these higher risk pregnancies. And beyond the direct health impact, there exists the socioeconomic impact of limiting women’s ability to further their education, employment, and social advancement.

The following three 17 year old patients, illustrate some of the current challenges facing young women in Ecuador:

Mavia* is 17 years old and works in the clinic as part of the janitorial staff. She recently retook the equivalent of the SAT’s and is awaiting her results next week to determine if she can apply to university to study nursing or to become a lab technician. To qualify for the program she needs at least 850 points on the exam. The last time she took it, she got 816 points. She’s concerned because each semester will cost $500 (the Ecuadorian currency is the U.S. Dollar) and doesn’t know if she’ll be able to study and work at the same time. However, she’s optimistic about the future and isn’t willing to give up on her dream easily.

Daniela is 17 years old and belongs to an indigenous group of Ecuadorians. She speaks both Quichua and Spanish. She’s been married for less than a year. Her husband travels for work and has been gone for about two months and is returning this week. She wants to discuss contraception options as she doesn’t want children yet. After a lengthy discussion she decides on Implanon and receives a prescription so she can purchase the Implanon and return to the clinic to have it placed.

Maricela is 17 years old and 38 weeks and 3 days pregnant. She started noting lower abdominal pains yesterday and presents today with her father because she thinks something is wrong. Her partner is currently at work. After a few minutes, it’s apparent that Maricela is in the early stages of labor. She receives extensive counseling on the symptoms of labor, what to expect, and went to present to the hospital.

*names have been changed

On the advantages of limited language skills:

As I sat in the car with our tour guide for the day trying to explain a word I didn’t know in Spanish, it occurred to me, I would be really good at Taboo in Spanish! The object of taboo is for the player to be able to describe a word without using other common words generally used to describe the primary word. When your language skills are limited, you have to get creative with explanations. This often includes basic or creative descriptions. As I struggled to describe the word, I realized that I wasn’t using any words that could possibly appear on a Taboo card. And after about a minute the tour guide guessed my word. Great success!!

In addition to making you a master in taboo, not fully comprehending or being able to speak another language helps make you a more active listener and more engaged in conversations. You don’t have the luxury of half-listening, hoping to remember some details when it’s your turn to respond. You have to engage every faculty and sense. The infliction, body language, tone all help to convey the meaning and give you clues when the topic/words are unfamiliar. This is important because you have to be judicious in your use of the phrase “I didn’t understand that” or “could you repeat that.” Just as when you’re having a phone conversation with someone in your native tongue and you can only ask them to repeat something they said a couple times before you, out of social convention and a willingness for the conversation to move forward, just let it go, so goes the courtesy of not making someone speaking in a foreign language repeat everything they’ve said because you’re learning. Sometimes, you may not get it all but that’s okay. Unless it’s something vitally important, do the best you can, keep a smile on your face, and use your body language to convert you’re engaged and listening. When you let go of expectations of perfection, you can enjoy the process and relax. And remember, there’s always Taboo! You’ll rock that!