Written by Deepika Parmar, MD, PGY-2 at Kaiser Permanente Oakland Pediatrics Program while on Global Health…

Global Health Rotation: Kenya – Jake Scott, MD

Written by Jake Scott, MD (a third year Internal Medicine Resident from Kaiser Permanente, Oakland while on a global health elective in Ugenya, Kenya with the Matibabu Foundation. )

I volunteered for the Matibabu Foundation in rural Kenya in April of 2014. I was based in the small village of Ukwala, in the Ugenya district, which is located in western Kenya, along the eastern side of Lake Victoria and the Ugandan border. It was an unforgettable trip for many reasons and I’m very grateful for having the chance to have gone, which I could not have done were it not for the generous support of Kaiser’s Global Health Program.

Since the age of 15, I’ve been fortunate enough to travel abroad several times. Throughout my travels I’ve always found the most rewarding part to be the people. New sceneries are often fascinating, but the most salient memories of my trips have always been the people I’ve met. This was definitely the case in Kenya. Everyone made me feel welcomed and they couldn’t have been more friendly and gracious. I stayed at a Catholic Parish where two priests were residing. They both had a really good sense of humor and the three of us had a great time together. I ate dinner with them most nights. Prior to starting our meals, of course, the priests would say a prayer. I’m actually not religious but I tried to follow along with Sign of the Cross, to be polite. On my first night, one of the priests noticed that I was fumbling a bit with the motions and he immediately asked me if I was religious. When I told him that I wasn’t he just laughed. He didn’t seem to be bothered by it all; he just found it amusing. The priests often took me with them to dinner parties as their guest and everyone always made me feel right at home.

In addition to the priests with whom I lived, I also felt exceptionally welcomed by the kind staff at the main hospital and at the various clinics. They were all very helpful and patient and many of them took a lot of pleasure in teaching me the local Luo language. (This is the language spoken by the Luo tribe, or ethnic group, which resides in western Kenya, as well as parts of Uganda and Tanzania. It is the third largest tribe in Kenya. Interestingly, President Obama’s father’s family is Luo, which is something I often heard mentioned.)

The clinical cases in which I was involved were astounding, in terms of the variety of pathology, the severity of illnesses, and the vast number of patients. I have been generally interested in infectious diseases (ID) ever since working as an HIV test counselor in San Francisco back in 2002. (I will be starting an ID fellowship this July.) Despite this interest that spans more than ten years I actually saw far more HIV cases in Ukwala on one very busy morning than I had probably seen in my entire career. The large volume of patients I saw on one of my first clinic days in Ukwala—approximately 75 HIV-infected patients, from nine o’clock in the morning until two o’clock in the afternoon—of course prevented me from engaging with the patients in significant depth; nonetheless, I was directly involved in assessing and treating them. Although a portion of the patients unfortunately met the clinical criteria for AIDS, and likely had certain opportunistic infections, such as CMV retinitis, tuberculosis, cryptococcal meningitis, and disseminated mycobacterium avium complex, I was impressed by the large number of patients that seemed to have their HIV infection fairly well controlled. For a number of complex reasons, the Ugenya district has an alarming prevalence of HIV. It is difficult to accurately determine the exact prevalence in the area, due to limitations in the infrastructure of the area’s public health, but the consensus I heard from the most experienced HIV clinicians and outreach workers in the area is that the prevalence is approximately 20%, which is the highest in the country. Put another way, it is estimated that one in five people (of all ages) are infected with HIV in the Ugenya district. This is a staggering figure. According to the Preliminary Report for Kenya AIDS Indicator Survey, the national overall prevalence in 2012 was 5.6%.[1] (This is compared to a United States HIV prevalence of roughly 0.4%, or 4 out of 1000 people, as of 2009.)[2] There have been significant improvements in both the Ugenya district and the Kenyan national prevalence, however, and I met several dedicated people who are working hard to continue to make headway in the face of enormous social, cultural, and economic forces, such as a general aversion to condom use, the normalization of polygamy, the Lake Victoria fisherman and truckers who spend their money on sex workers,[3] and, of course, the severe poverty, lack of adequate education, and dearth of necessary resources. There are several massive challenges to overcome in order to continue to reduce the rates of HIV transmission in the Ugenya district but I certainly saw a concerted effort on the part of community health outreach workers and the clinical staff.

I spent the majority of my time at the Matibabu hospital, which was opened in January 2012. It is a small hospital by American standards but it is impressive. Dr. Fred Okango, who was my attending physician, serves as the medical director. He is a warm and patient man with several years of experience, including a harrowing stint in South Sudan. The two young, hardworking “clinical officers”, Peter and Evans, are “mid-level” clinicians who are the ones directly involved in most of the patient care. Despite having gone through a fraction of the training that American physicians go through, they essentially serve the function of physicians. I was immediately impressed by their clinical acumen and their engagement in the care of patients, many of whom were quite ill. These clinical officers were able to efficiently and effectively manage certain typical presentations, such as malaria and helminthic infections, but they admitted to me that they were not entirely comfortable with managing certain chronic diseases, such as hypertension, congestive heart failure (CHF), and diabetes. Since these diseases have made up a significant portion of the cases in which I have been involved as an internal medicine resident, I took the opportunity to discuss these topics with them in depth. Together, we managed several cases of severe CHF exacerbations, hypertensive emergencies, and outpatient diabetes cases. Using our patients as examples, I set aside time in our busy work schedules to teach them pertinent physical exam skills, bedside ultrasonography, and current hypertension guidelines. I also made recommendations to Dr. Okango and the lead pharmacist for additional medications to acquire, and I developed a CHF protocol for the hospital. My time at the hospital also coincided with the development of the hospital’s infection control committee, which dovetailed nicely with my interests and experience. The infection control committee director and I worked together to develop a means of tracking hospital acquired infections, such as catheter associated infections, and we used the whole month to focus everyone’s attention on the importance of hand hygiene.

The month that I spent caring for patients in Kenya was remarkably educational for me. It was challenging, of course, to orient myself in such a completely different work environment, but adaptability is a skill that I value highly. I consider the time I spent in Kenya being directly involved in managing illnesses with which I had little or no prior experience, such as malaria and mycobacterial infections, to have been a formative part of my training overall, especially as I embark upon a career in ID. Furthermore, given the general lack of many of the medications and tests upon which I rely at home, my experience working as a physician in Kenya also forced me to rely on my own clinical reasoning and physical exam skills like never before. Rather than having the luxury of ordering a battery of expensive tests to acquire more information with which to make clinical decisions, I had to work with the patients and our team to make the best attempt at a diagnosis with very limited means and information. This often required prioritizing my management plans, and because most patients were paying out of pocket, cost consciousness was always a significant factor.

In addition to making meaningful connections with the people I met, and developing valuable clinical skills, I also got the chance to explore parts of Kenya. I spent one weekend traveling by myself to Mt Elgon, the second tallest mountain in Kenya, standing at 14,177 feet, which I ascended. The scenery was very unique and I saw certain wildlife such as baboons, waterbucks (large antelope), warthogs, and countless birds. I also explored a few of the mountain’s many caves, including the infamous Kitum cave. (Two tourists who visited this cave, back in 1980 and in 1987, died from the incredibly lethal Marburg virus, which is thought to have been transmitted by the cave’s copious bat guano. This epidemiological mystery was dramatized in the book, The Hot Zone.) Fortunately, I made it out of the cave alive.

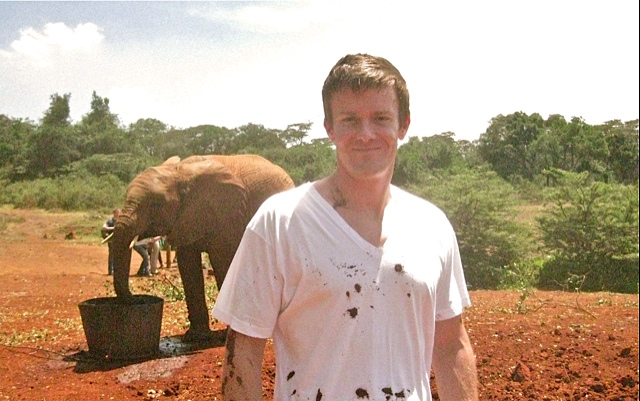

Prior to departing, I spent a few days in Nairobi. One of the highlights of the trip, as a tourist, was the elephant orphanage. It is basically where young elephants who are found to be alone out on the wild, usually because their mothers were killed for their ivory, illegally of course, are taken in and nurtured, prior to be gradually reintroduced into the wild later as they reach their teenage years. I got a bit too close to one of them that actually used its trunk to spray me with muddy water, which was perfect timing, considering that I was wearing the clothes at the time that I had planned to wear for my 36 hour long trip home. (I changed of course).

In closing, the month that I spent in Kenya was one of the most incredible experiences of my life. I really appreciate being given this opportunity and am sure that it significantly contributed to the development of my career, and introduced me to some wonderful, lifelong friends.

[1] http://www.scribd.com/doc/167580994/Preliminary-Report-for-Kenya-AIDS-indicator-survey-2012-pdf

[2] http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/2010/surveillance_Report_vol_17_no_3.html

[3] http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/apr/25/aids-and-hiv-uganda

Though it was short duration being with you I must say we gained alot from your teachings and instructions, you are always welcome to Matibabu Kenya

My brother suggested I might like this website.

He was totally right. This post actually made my day. You cann’t imagine just how much time I had spent for

this information! Thanks!

I just like the valuable info you supply to your articles.

I’ll bookmark your weblog and check once more here regularly.

I am quite certain I’ll be informed lots of new stuff right

right here! Best of luck for the following!

My Elgon isn’t the highest point in Kenya.